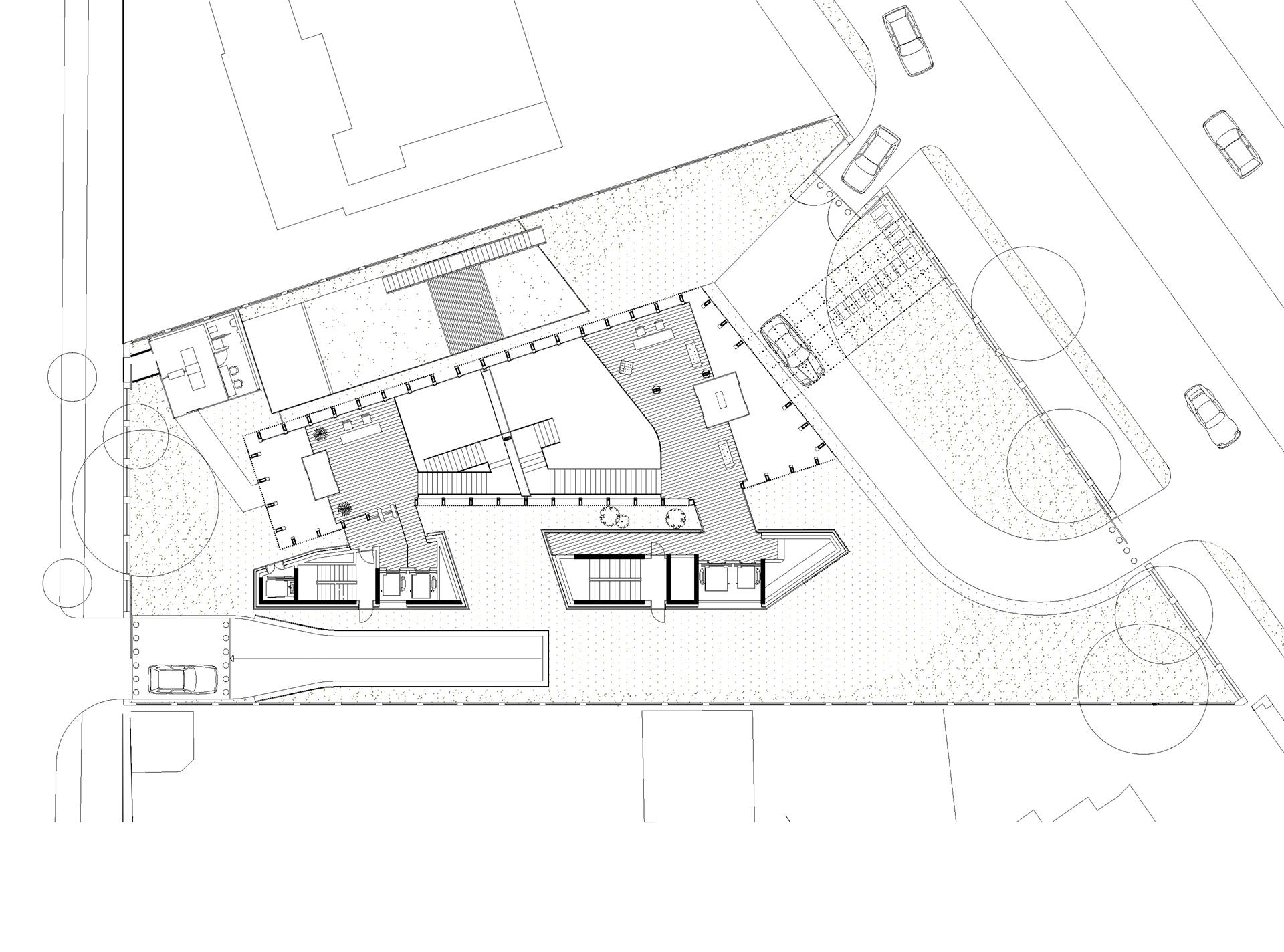

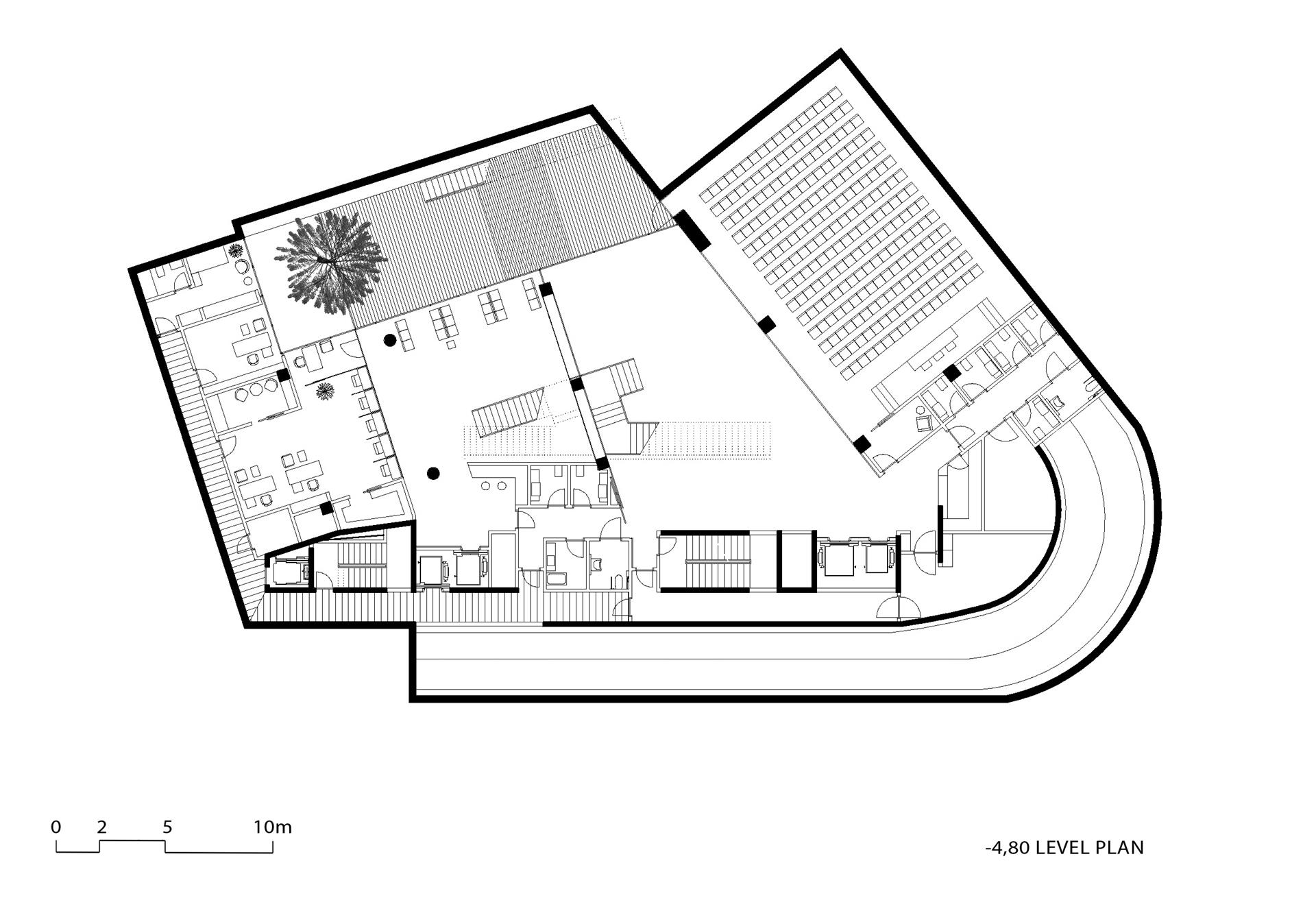

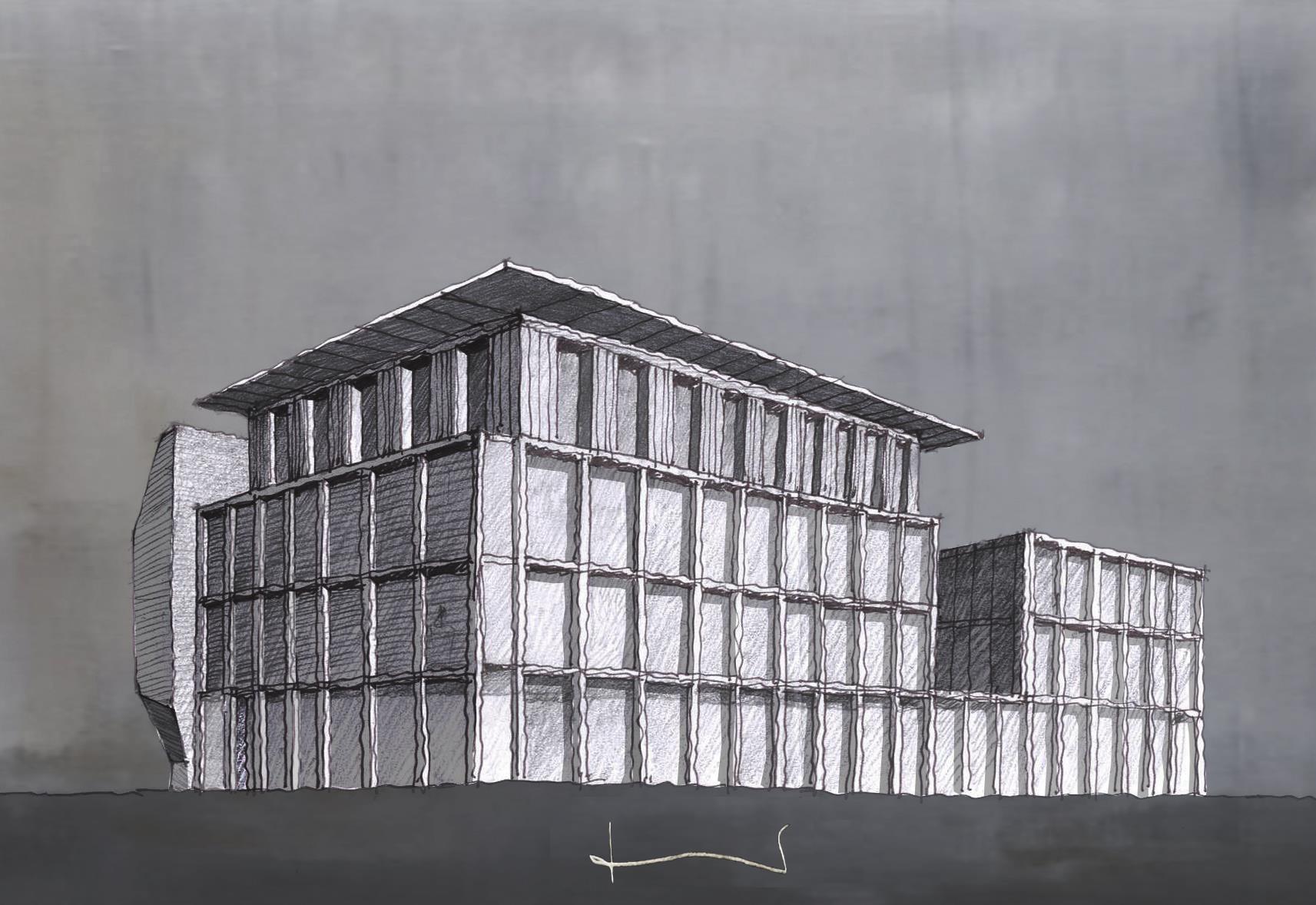

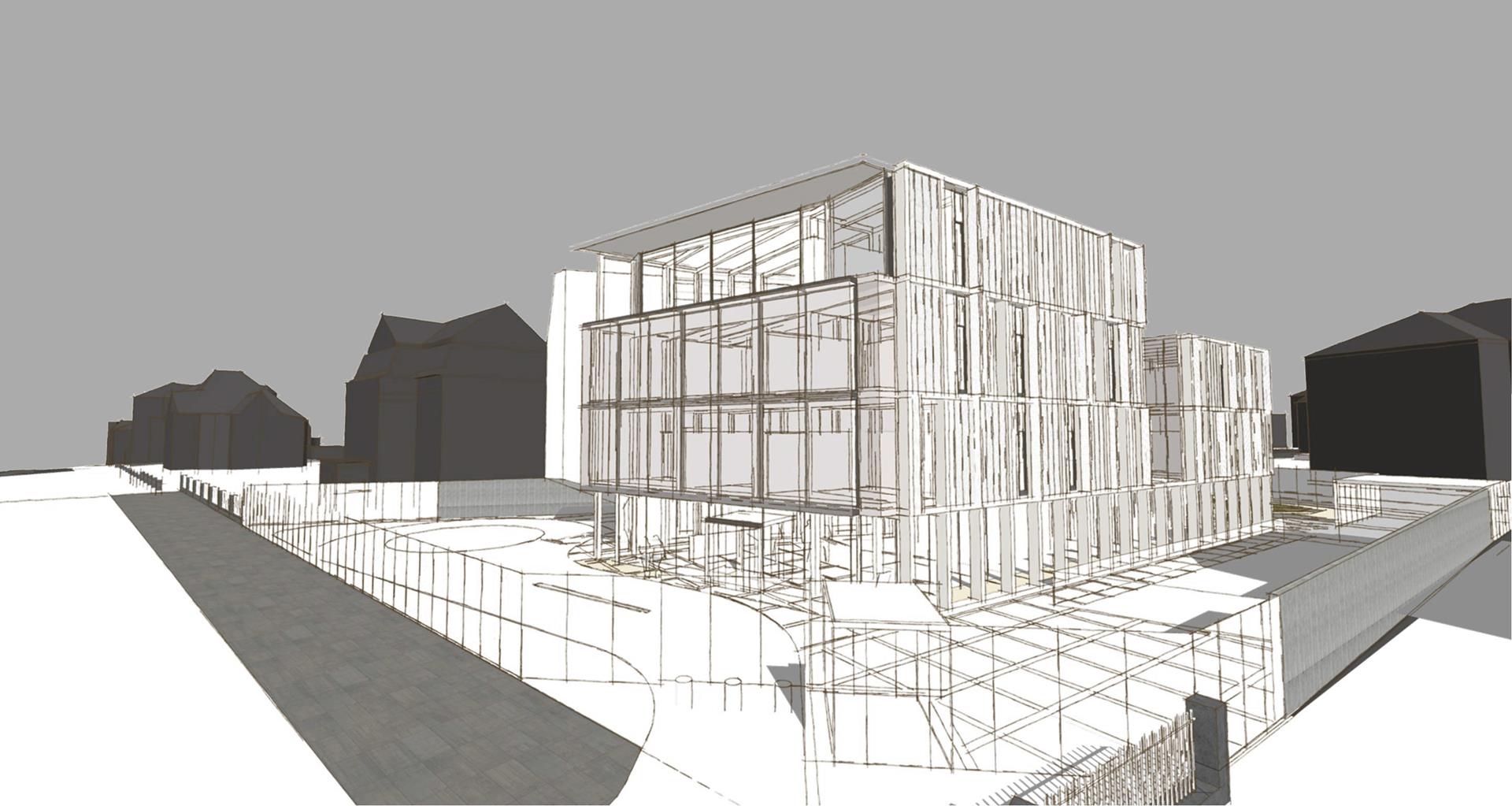

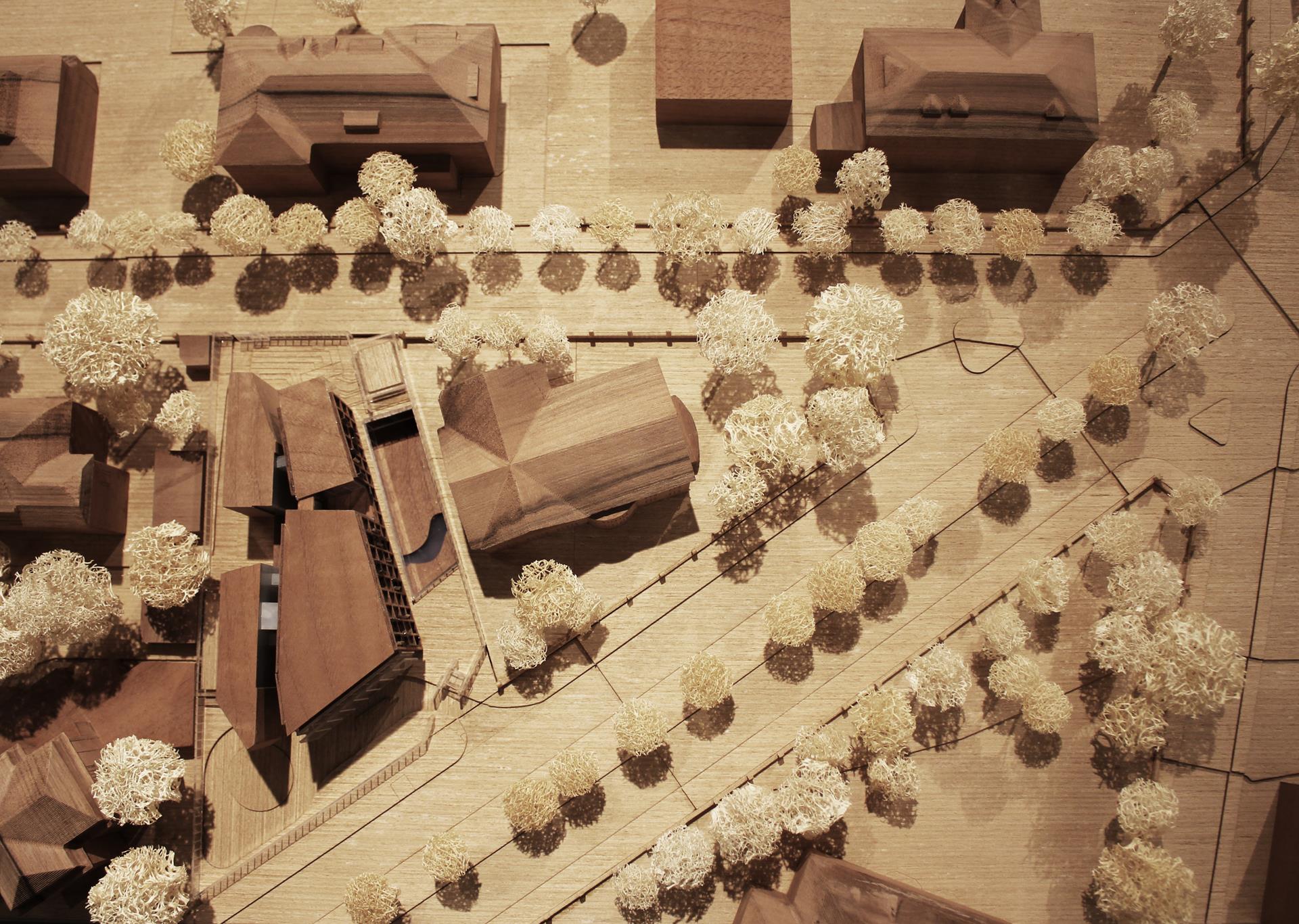

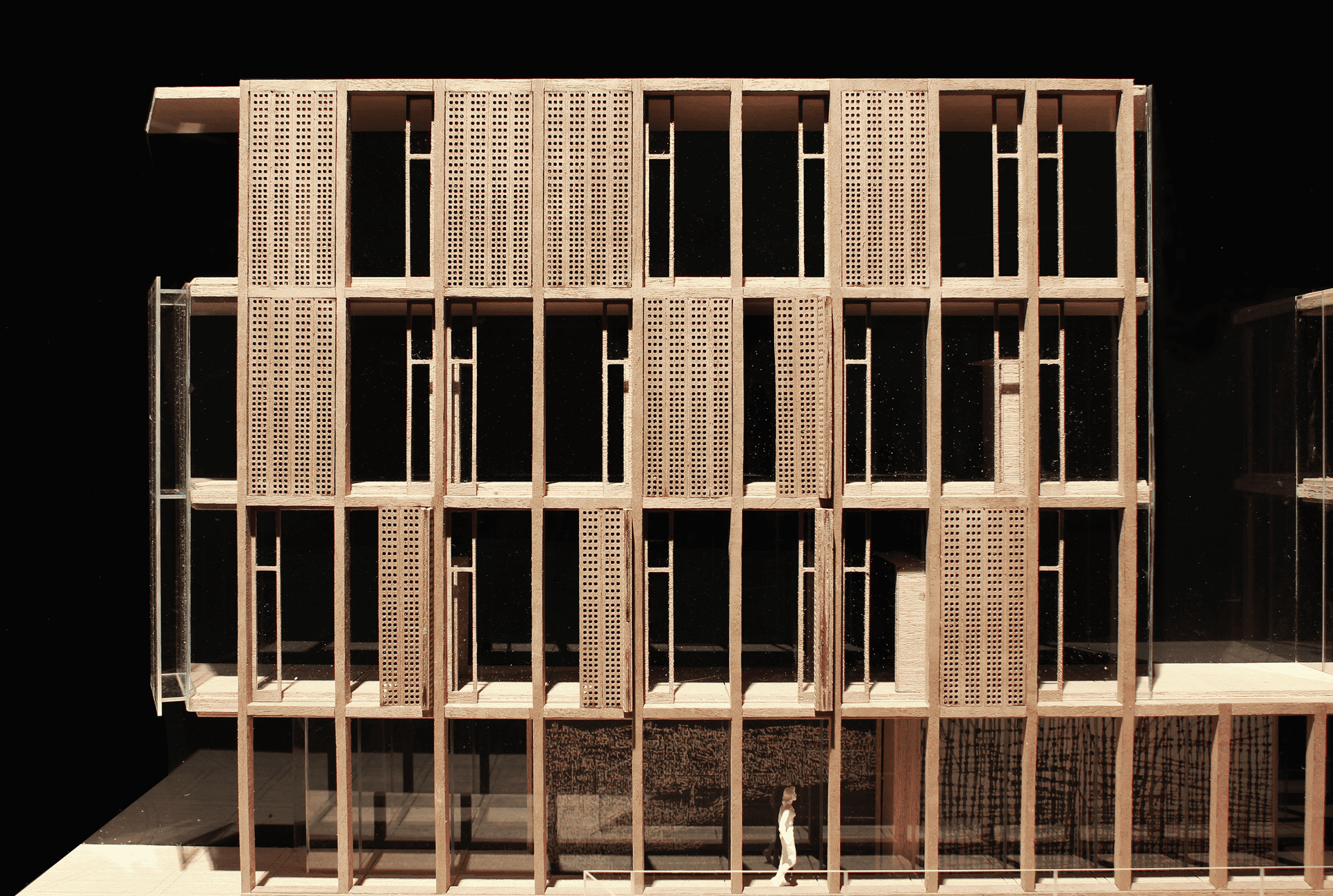

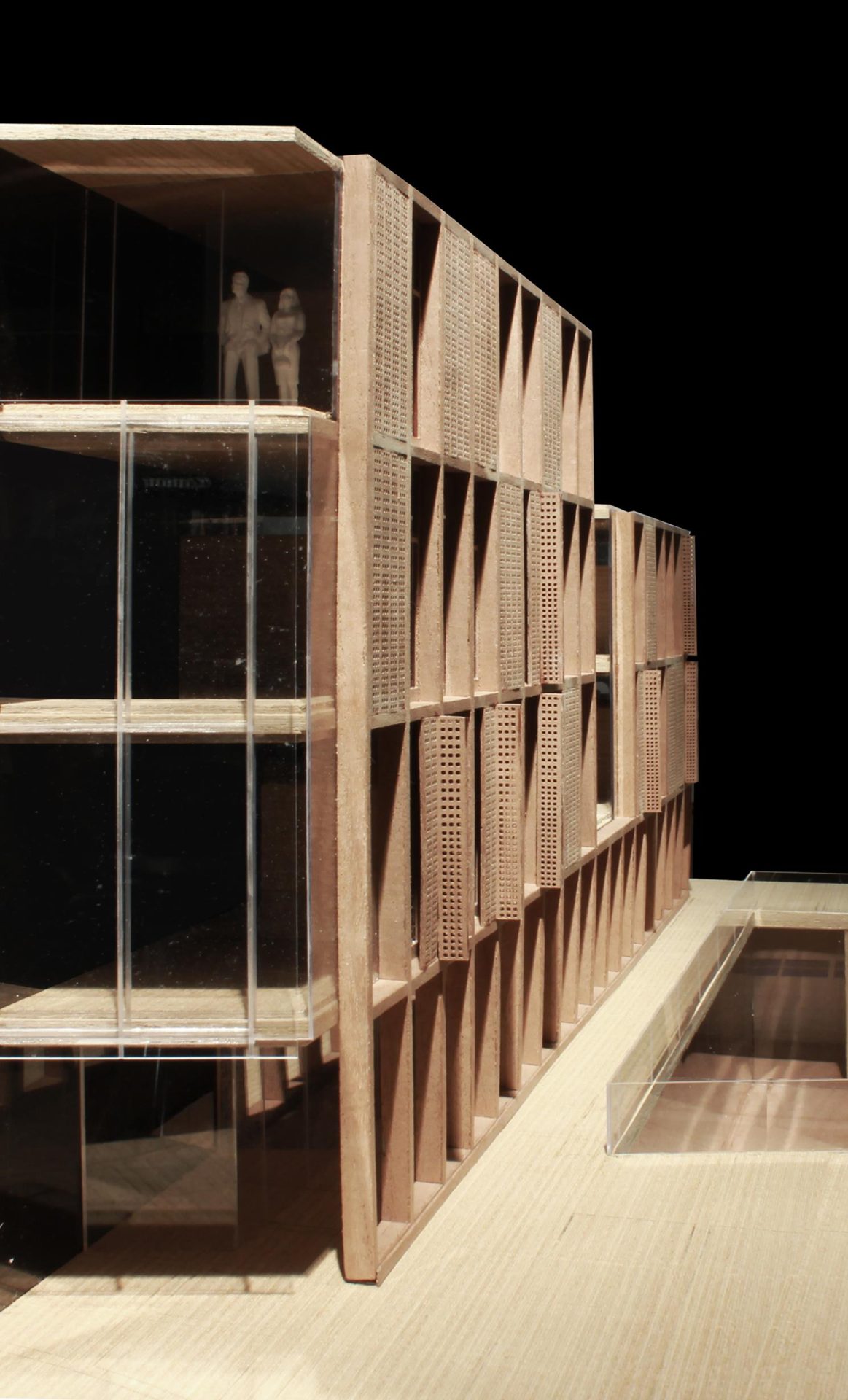

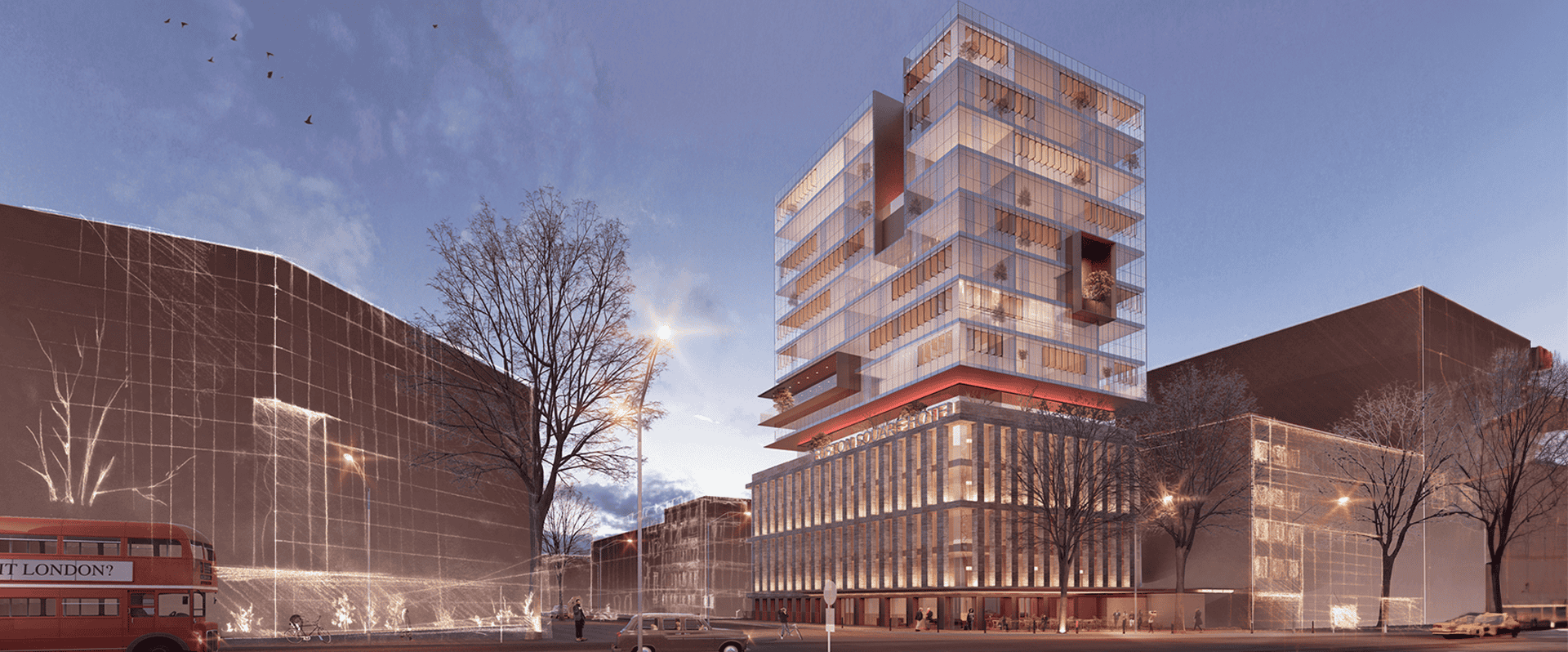

The design of Turkish Chancery in Prague is driven by the question of how to belong to the site while facing the discourse about being “Turkish” in a foreign land. The answer has been searched in the structuralist approach of the modernist interpretation of Turkish regionalist architecture which is constituted on the structural carcass used as a construction technique in traditional Turkish houses. The building is fragmented into four volumes to be able to merge its site while having this structural grid as an abstract image about Turkish architecture.

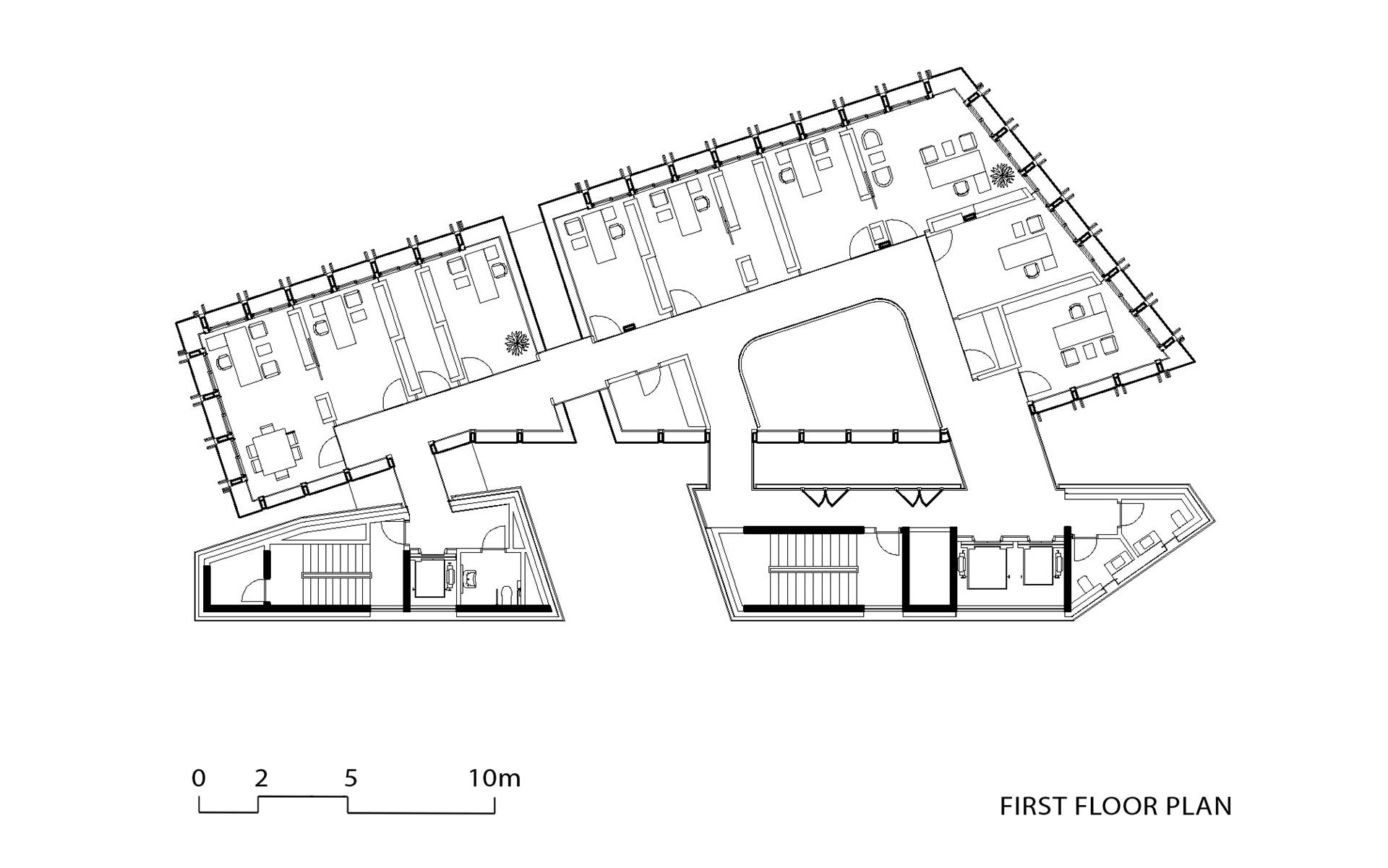

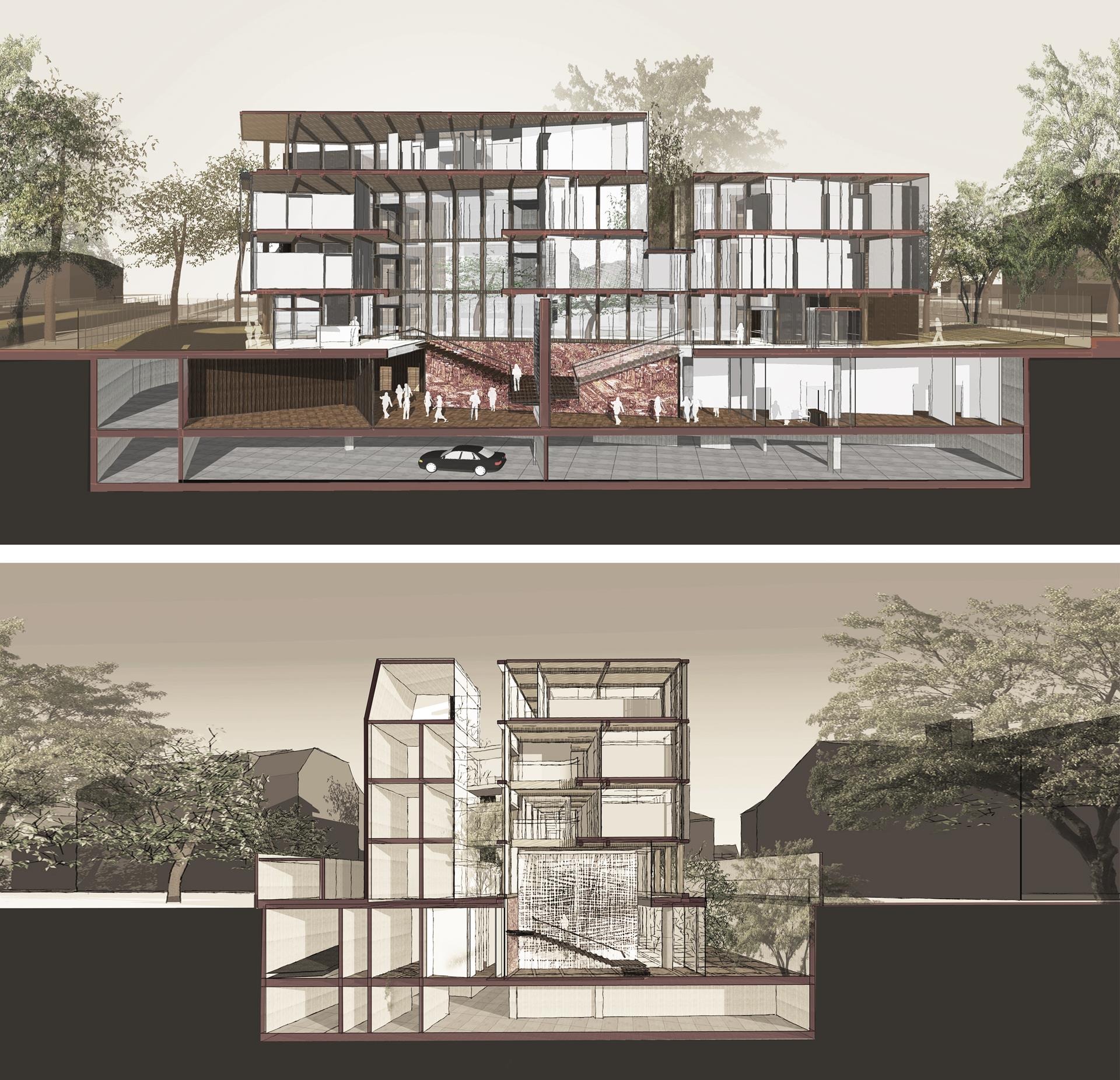

In a city like Prague, where most of the year there is not much daylight, one factor that becomes very important is designing the surface of the building to let daylight in and penetrate through to the interior as much as possible. As the building is fragmented into four, the surface area exposed to daylight is increased. The alike functions are gathered together and the surfaces are made more transparent while the parts of the buildings are connected through transparent passageways.

The physical relation of the building to its surroundings plays an important role and the building’s respectful approach to its characteristically quite specific neighbourhood also becomes one of the major concerns of the design. The geometry and ornamentation of the Cubist movement, the first thing that comes to mind when spatial culture of Prague is considered, have in their unique way been determinant on the total design of the process.

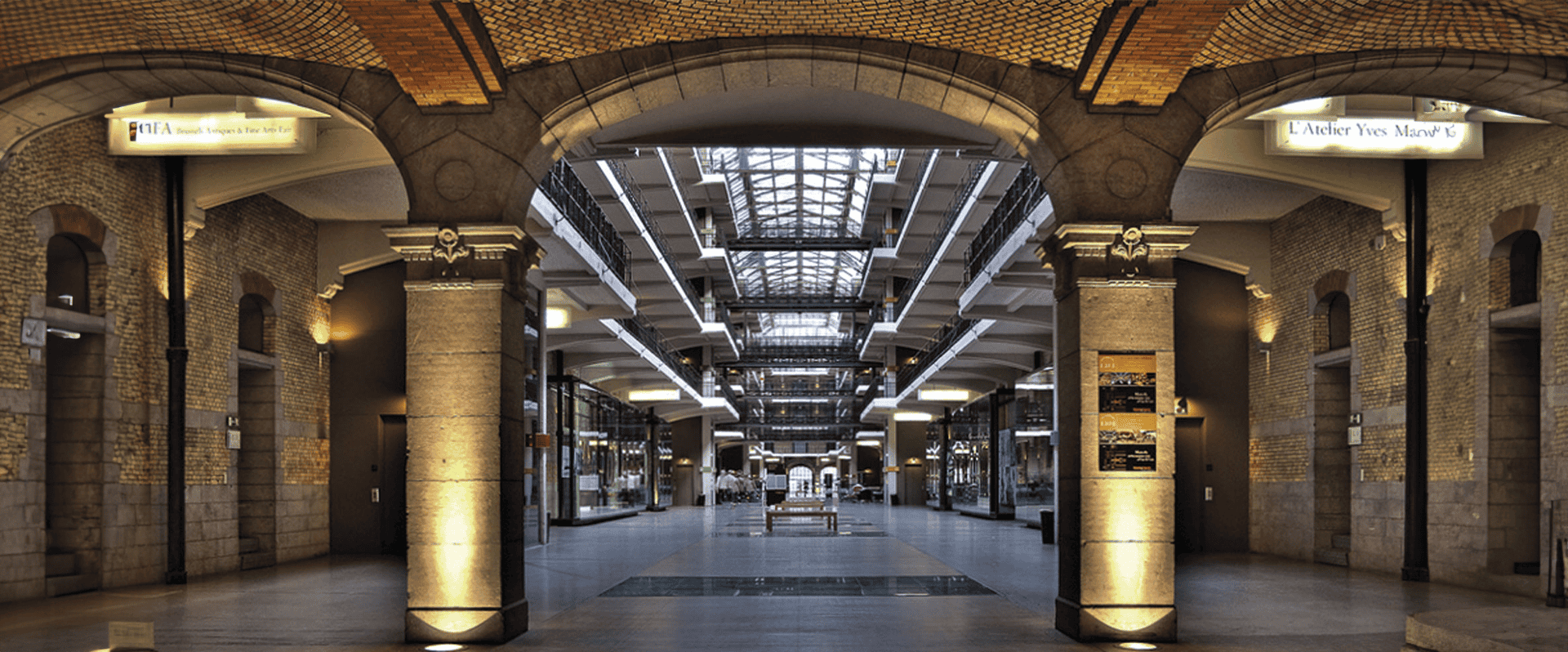

A similar interpretation and synthesis of Turkish tradition and local values is carried on in the interior design. The traditional layout of the Turkish house as rooms around an anteroom, the “sofa,” cerates the main structure of the planning. For the interior surfaces, strength of order and rhythm created by the grids is widely used just as in Turkish traditional interiors, which is also valid in many Chech buildings. Use of Turkish artworks together with cubist accessories enrich the spaces.